Hi! Excited to share this with you — the first chapter of my new novel MORSE CODE. I feel weird putting a picture of my head in the banner photo but after thinking about it, it makes sense: the photo is a still from the 30 minute pilot I produced in 2023 with Randa Newman and Travis Nicholson, which won several awards including Audience Choice Awards at Nashville Film Fest, Berlin Shorts, Best Lead Actor at the NYC Television Festival, and more). The novel I’ve written is based (as many of you may know) on the pilot and features the same world and characters — it was a challenge to adapt the screenplay to the novel form, and as to how well I did, I suppose you’ll be the judge.

It would mean a lot to me if you left a short comment. If you’re reading this in your email, please take a second to jump onto Substack and drop one there. Putting this piece of writing out here is uhm, fairly terrifying to me, and I’m making my decision of what to do next (keep releasing chapters on Substack? Hole up and try for traditional publishing? Scrap the whole thing and enroll in welding school? [don’t laugh I’m this close]) based on how this goes.

Okay enjoy!.

Morse Code

Chapter 1: Singer of His Own Song

There are two kinds of singers in Nashville. The first one sings his own song. The second, someone else’s.

First, a salute to the second: O happy creature! Useful friend! Born with a sacred power, old as wind; a shiny instrument someone shoved in your neck and you didn’t even have to learn the fingering.

You Lukes Zachs Zaks Bryans Browns. You gallant thoroughbreds. Team players! Attainably handsome, marvelously malleable, you are twenty nine and fit as fuck. You chosen wonders, company men. You have it all: twang, face, connections. You just need the words — the right ones, in the right order.

You need the song.

A good singer is like a good actor: give him the words and he’ll do the rest. He’s like old Phalaris’ Bull: the sound he makes is lovely, as long as someone inserts the raw material first.

What luck! An entire industry, poised to assist: balding wordsmiths with forty-nine cuts, square-jawed managers with deep vees and bleached teeth, seasoned producers, melody men, hairdressers, stylists, social media consultants, voice coaches, personal chefs. An armada of helpers, co-dreamers, hired believers, all looking for the One Who Sings.

We know the story of the plebe’s ascent to plenty. It’s as familiar as the lyrics to a Taylor Swift song. It’s the Season 7 Winner. The Streisand remake, the Behind the Music episode we watched over and over.

Boy has voice. World loves boy.

It’s a fine story.

This, is not that.

This is a story for the other kind: that inspired idiot, the singer of his own song. The closed loop of the music business. The one man band. The crooked tree. The confused patient who, hearing voices, refuses to see a doctor. Who traces the lineage of his misfit tribe from Jason back to Joni, Bob back to Woody and back further, to that forgotten clown alley of wandering minstrels and mountebanks whose self-sung paeans to life’s woebegone joy predate the vinyl scratch of recorded sound.

Tom, Leonard, Kurt, Neil, Jerry and a hundred self-penned singers. Some of those singers are good, sure. But good singing isn’t the point. Good enough singing is. Good enough to bear the ballast, to convey the cantata, to reveal the reveler. In this world, our world, song and singer are parts of a whole. River and ocean. Tempo and tambourine.

A song sung by its maker is no longer the stuff of mere entertainment. It takes on a sacred character, because it comes from a sacred source. What is that source? Nothing less than a human being, a singular soul, frail and fraught, unique among his eight billion roommates, born shivering and alone, whose confused and desperate need to understand himself and his life and the short mean muck he swims through has assumed the form — not of a poem like Goethe, or a symphony like Mahler, or a novel like Tolstoy — but a song. Just a song, sung with all the gorgeous imperfection of one individual life. This man is a prophet and fool, and his mumbled message, doubtless faulted, limited in scope and audience, destined to fail, is yet more likely to save the world than all the number ones in Nashville.

If great singing is what you’re in it for, Simon Morse is not your man.

But look at him try:

Eyes closed, squinting under a rakish mop of old yellow hair, oblivious to everything but the sound coming out of him.

The conviction, a confession. He’s one of those sad fools who means what he sings. No longer young. Not yet grey. Hesitating at the exit of modern life’s second adolescence.

That’s what this story is about. A person between. Genres, chapters, seasons. Maybe you can relate.

He sings:

I wake up and it’s already started. My mind hissin like a snake in the garden

You can. You came from somewhere. You’re going somewhere else. Where? Simon is trying to understand too.

He sings:

It’s telling me I won’t amount to anything

His body, wrapped in worn denim, pulses like one of those animated tubemen you see on the side of the road, jerked in a patternless dance by the current moving through him.

The tips of his fingers slot into place between the pocked frets of an abused acoustic. Not quite nimble but we see the precision. The kind of hard-won expertise born of repetition.

He strikes the strings in lockstep with the hi hat. A descending figure.

He sings:

Wish I could go back to sleep instead of living in this bad dream

The band is cracking like a wet whip. The bass player, bald, slender, pins down the chords like a tent in a storm. You’re not watching closely but if you were you’d see his eyes under the shadow of a tall trucker cap flick to Simon’s hands for the changes.

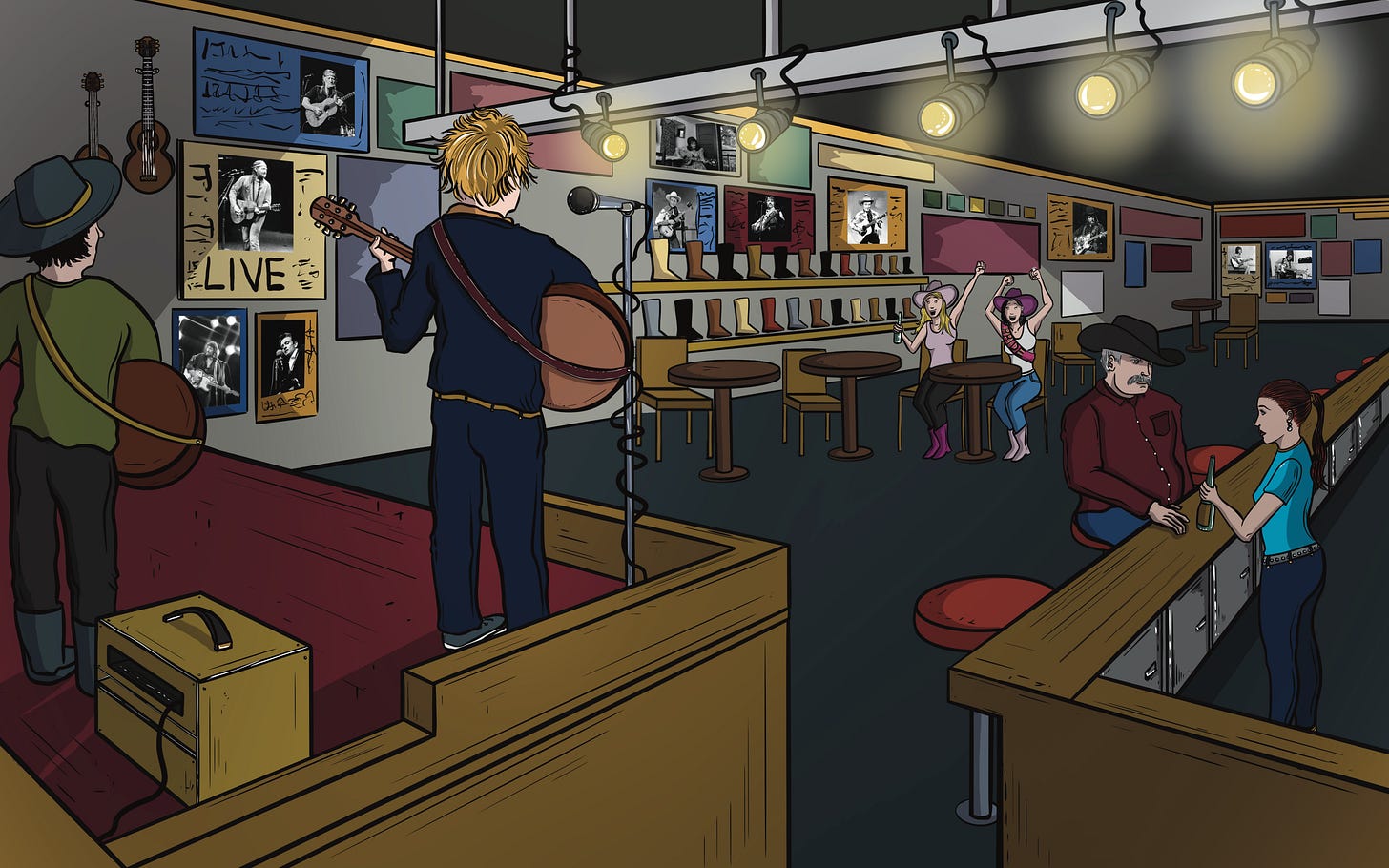

The stage, Robert’s Western World. Maybe you’ve been there.

Something of a hallowed institution — on the continuum of country venues loved and lauded it sits between the Ryman and the Station Inn. Robert’s. Last of the old school holdouts. The one place downtown where you still might catch a local. Maybe you were there once, on say, a weekend visit, eating the fried boloney sandwich on the bartender’s recommendation. It tasted better than how your mom made it when you were a kid. You remember now. You dabbed the corners of your mouth with a paper napkin, watching the best guitar player you’d ever seen, playing for tips.

You’re sitting there. At the first table, tall and round, butted up against what passes for a sound booth. Your shoulder is so close to the wall of boots for which Robert’s is famous that you smell both the leather they’re made of and the feet that once wore them.

You wonder if the boots are really for sale. You see the tags but maybe that’s all part of it. The Nashville illusion. The bar’s not full and you don’t know any of the songs, so you have a look around: to the wall crammed with the junk charms of country music past: a kaleidoscopic woodcut singing the praises of Bill Monroe. Old Hatch Show Prints advertising concerts nobody remembers; guitars, decorative and stringless, crawling like beetles over paintings, photos, warnings; a sign advertising a brand of beer that hasn’t been made for thirty years.

In the corner, over the drum kit, hangs an American flag, yellowing, surrounded by hundreds of black and white photos: country legends, favored patrons, forgotten also-rans. Each frame affixed to the wall with two Phillips screws, north and south.

You look down at the drummer smashing his way through, announcing the second verse like a dropped dish. You don’t recognize the man singing, rising up on his tip toes, rocking back and forth like a bird on a swing.

It’s three o’clock in the afternoon at Robert’s. Simon shouldn’t be here. Even you can tell. He doesn’t fit. There’s no swing in the beat, no twang in the tone. He’s an intruder, a silhouette: the window glass behind him dumps into the bar a load of afternoon light unpinked with neon. The pink is on the people. You can see them on the sidewalk through the window. The clothes, the hats, the sashes.

Sometimes Robert’s is full even this early, just not today. But let’s strike a hopeful note — patrons though few, they look like they’re paying attention. The bar, dark at mid day, smells like old desire — sweat and wood and spilled beer — and though there’s something about Simon that makes it clear he doesn’t belong, he’s not exactly dismissed either. Not exactly.

He sings:

Maybe it’s all in my head

Simon kicks his way into the bridge singing something about still having a chance and a choice and not being dead yet. Over at the bar a man with a face like crumpled paper twists on his stool, lifts a crisp black cowboy hat from his silver head, replaces it. He bends back into his beer, the look on his face downgrading from disappointment to dejection.

Onstage, Simon urges himself through a last chorus, the band building behind him. His body gyrates like it’s sprung a leak, the song a spell spinning out from a place maybe darker than this dark bar, flying around the room like the disturbed angels from an unearthed ark.

Maybe it’s all in my head

He howls.

Maybe it’s all in my head

Every confessor hopes for salvation.

Maybe it’s all in my head

Suddenly the song arrives where it started. One last crash and the lid snaps shut.

Is the crowd stunned? A silence like a held breath lingers a beat longer than feels polite. You almost expect someone to say Amen. Instead:

“Take off your shirt! Woooo hoooo!”

Simon comes back as though from somewhere far away. What’s going on?

He frowns through the scattered applause, looking to see where the shout came from.

She’s whipping a bar towel around her head like a cowgirl’s lasso, cackling with approval at her own jibe. She wears a crown of glitter — the official texture of downtown Nashville — in the form of a discount cowboy hat a size too small. Her cheerful chest is wrapped in a royal sash of plastic satin. Simon can see the inscription from the stage, in delicate cursive:

One Last Ride ‘Fore I’m the Bride

Her half dozen companions bellow assent from a shared skein of identical T shirts, reeling together to the click of bottles, sweat darkening the places where skin meets fabric.

Simon feels no slight. This is their bar, not his.

He hurries a thank you into the microphone and looks around for someone to hand the guitar to. He’s gotta get out of here. He’s supposed to be somewhere. And he’s late. He can tell because of the sudden sweat. Not rocknroll sweat. Tardy sweat.

Simon fist-bumps the drummer and sidehugs the bassist and wonders if leaving this borrowed guitar onstage is too much of a dick move. He’s already pulling it off his shoulders.

Suddenly a bearded man in a vintage Mountain Dew Tee shirt beams at him from the bottom of the stage stairs.

“Benny!”

“Sorry I’m late,” Benny says.

Simon, grateful, hands over the guitar. Benny receives it like parent and prodigal.

“Thanks for covering bud.” he says, shouldering the guitar and nodding to his rhythm section.

Simon is already gone. He takes the stage stairs in two strides, house music keening the junior form of Hank overhead, and hurries across the hammered dance floor to settle up with Barb.

He’s pushing his way through the thickening idlers when he feels a slap on his back. A little too hard. Simon turns to see the fingers of the hand re-form themselves into a thumbs up. He follows the hand up from the arm to find it attached to a heavy middle aged man in shorts and flip flops and a Joy Division Tee.

That guy doesn’t belong here either. Something of a comfort.

The bartender looks up from the beer she’s pouring.

“I like the new one, Simon.”

Simon moves toward her, glad for the oasis. Barb has been tending here since the Brasil Billy days. Cigarette-thin and smiling to wake the sun, she swipes the bar with a practiced motion and turns toward the cash register.

“Thanks Barb—“

“Hey.”

Another hard back slap. What is it with these people and bodily contact?

Simon suddenly realizes he’s inadvertently grabbed the stool beside the crumple-faced man with the hat.

The man looks into Simon’s face for a long beat, souring.

“You call that country?”

Two out of three in the heckler-to-fan equation. First the woo girl and now this guy. Fucking downtown.

“No sir,” Simon tries. “I think you call it Americana, err, folk… roots…acoustic…”

Did the room just get quiet?

Simon shoots a look toward the rear door, to freedom, to the appointment he’s late for, now back at the cowboy with his old man face draped in a sheet of angry expectation. Expectation of what? An apology? Simon would apologize. Anything but conflict. He wants to say Sir I realize this place is your place and not mine and of us two you are the one who belongs. I am the intruder. The thing is, I needed the money. I always need the money.

The cowboy grunts.

“Shut up, Carl,” says Barb.

She puts a few bills in Simon’s hand. “For filling in. Sorry about the woo girls.”

“Well. Thanks for keeping em to this side of the river.”

“Won’t be long before they learn how to swim!’ Barb disappears.

Over the loudspeaker the band kicks off the next set. Here’s A Johnny Paycheck song, says Benny over the opening bars.

He has the kind of voice that sets a mind at ease. True country. A little Saturday night, a little Sunday morning.

The room settles back into a comfortable posture as Simon hastens to the stairs that will take him to the alley where waits his bike and the water meter it’s chained to.

Definitely gonna be late.

Do you wonder what Simon’s late for? Do you want to read the next chapter?? Let me know in the comments below! Thanks ~ Korby

I'm intrigued by all the adjectives you selected to start out with and set the tone, and all the comparisons. The bar scene was beautifully described and immediately pulled me in to being there in the audience, watching, listening, and relating to Simon. I love it and can't wait to read more!! You've sharpened your pen for this one, great writing.

Been waiting for this! And it did not disappoint. I’m hooked.